What is causing my knee pain?

Because the knee has the largest articulating (moving) surface area of any joint in the body and is weightbearing, it is not surprising that it is among the most commonly injured body parts. Knee pain is very common, with estimates it accounts for over 1 million emergency department visits and more than 1.9 million primary physician outpatient visits annually in the United States alone(1).

Knee pain can come from acute trauma, chronic overuse, or a combination. While a full evaluation of knee pain, sometimes coupled with imaging and a specialist examination is recommended, there are a few clues as to the cause of your pain. Here we review some of the common presenting symptoms and how these symptoms can often times point to a particular source. By reviewing this information, you can be more informed on your condition and have a better idea about treatment options.

Acute injury from trauma or overuse

Acute trauma is typically easy to identify. Acute trauma is most simply defined as something abruptly going wrong. A collision between players, a skiing accident, and a fall from a height are common examples of acute trauma. But contact with another player or an object is not required. An athlete who experiences pain immediately after jumping, landing, cutting, squatting, slipping, or sprinting is classified as having experienced acute trauma. Pain from acute trauma typically stops the athlete from completing their intended activity, and the resulting injuries are often accompanied by inflammatory sequelae such as bruising, swelling, or joint effusion (fluid).

Acute pain associated with overuse (or “overuse trauma”) generally refers to pain that develops or increases abruptly after excessive activity. Overuse trauma from excessive activity is associated with a progressive pain pattern that causes increasing functional limitations or complete cessation of activity.

Both acute injury-related knee pain and acute overuse pain have different causes and sometimes imaging evaluation with MRI is helpful.

Acute versus chronic pain

Acute and chronic pain are classically distinguished by duration. For most orthopedic conditions, pain for less than six weeks is usually described as acute or subacute, while pain lasting longer than six weeks is typically characterized as chronic. While the six-week threshold is arbitrary, it can be useful since many self-limited injuries heal by the end of six weeks with appropriate rest and modification of activities.

Another difference with chronic pain is that it typically has a more progressive pattern. As an example, chronic knee pain from a meniscus tear or osteoarthritis may initially only be bothersome at the end of the day or after vigorous activity, but may progress over weeks to the point where pain develops after simpler and shorter duration activities, and can even start to occur at rest.

Characterizing symptoms and the mechanism of injury

It may be helpful to ask yourself some of the following questions as it may point to a particular cause.

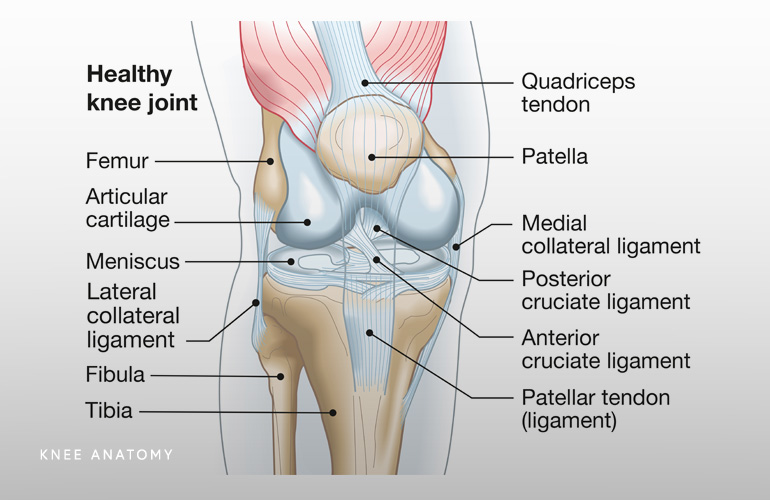

- What were you doing immediately prior to and at the time pain began? How were your leg and body positioned? The exact activity at the time of injury can help to determine the diagnosis. As an example, a basketball player whose knee buckles while landing after a jump shot, followed by rapid knee swelling, gives a history suggesting anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury. When patients experience significant pain or swelling without sport or work activity, a degenerative (wear and tear) condition triggering the knee symptoms is more likely.

- Did you have pain immediately at the time of injury or during exercise? Immediate pain with an injury or during exercise likely represents structural damage to the knee.

- If not immediate, how long after exercise does the pain begin?Delayed pain or soreness could still reflect an acute injury, with an example being the meniscus, with “micro trauma” to the tissue causing the onset of pain more gradually as the body’s healing mechanisms kick in. This delayed pain can also be a manifestation of cartilage contusion, muscle strains, or tendon inflammation. The length of the delay may have significance. As an example, pain after four hours likely represents a more severe injury than soreness after 48 hours (or a week).

- Is the pain intermittent or constant? Constant pain suggests either major injury or an active inflammatory/healing process. Intermittent pain suggests a more minor injury or possibly excessive activity in the case of an arthritic knee.

- Does the pain only occur with specific activities? Specific activities that trigger pain can be extremely helpful in diagnosing knee pathology. As an example, pain with prolonged sitting or when climbing or descending stairs is a classic part of the history of patellofemoral pain.

- Has the pain prevented you from performing (physical activity of choice)? Have you been able to resume doing (physical activity)? The answers to these questions help to determine how aggressively to intervene. When pain prevents sport or work activity, or even activities of daily living, more aggressive intervention is justified; if the patient has resumed activity, treatment can begin more gradually.

- If you have pain with weightbearing, does this pain resolve with nonweightbearing? Answers to this question help to identify specific sports injuries. As an example, patients with a meniscal or articular cartilage injury may experience significant pain with weightbearing activity but minimal pain when swimming or biking. Patellofemoral pain typically causes anterior knee pain only with running, walking down steps, or prolonged sitting with the knee bent. On the other hand, a severe injury causing an effusion is likely to cause constant pain. As examples, a torn collateral or cruciate ligament typically results in a constant aching pain that is not made especially worse by normal weightbearing.

- Is there pain at night? Pain at night suggests significant structural damage; conditions like tendinopathy or patellofemoral pain rarely cause night pain unless there is an associated tear. Pain at night is more common with bony injury, such as osteoarthritis or a significant intra-articular process like a stress fracture of the tibial plateau. Although much less common, bone tumors can present with pain that is worse at night.

- Does anything relieve the pain? Does anything exacerbate the pain? Factors such as weightbearing or twisting, going from sitting to standing, running downhill or walking down stairs may be indicators of a likely mechanism of injury and probable diagnosis.

Further questions to ask that may point to a particular diagnosis:

- Did you hear or feel a snap or pop associated with the injury? If the patient describes hearing an audible pop, ACL or other ligament tear is a major concern. Teenagers and young adults who sustain an acute meniscal tear may also experience an audible pop at the time of injury.

- Following the injury, did the knee immediately begin to swell? Was any bruising or redness noted? Rapid swelling following an acute injury occurs with bleeding into the knee joint, and occurs with significant tissue damage such as an ACL tear.

- Do you experience instability or a sensation of the knee “giving-way”? It is important to distinguish true mechanical instability from pain-mediated instability. True instability occurs when the knee subluxates or “gives way” during a routine activity (eg, climbing stairs, walking) without pain preceding the episode. Such instability occurs with ligament tears and patellar instability. Pain-mediated instability occurs when knee or other lower extremity pain inhibits motor nerves controlling the quadriceps muscles causing the knee to buckle. This can occur with any number of painful conditions.

- Do you feel the knee is locking or getting stuck in place? Locking of the knee suggests a mechanical block, as might occur with a meniscus tear or loose piece of cartilage. It is important to differentiate a true mechanical block from subjective symptoms of “grinding,” “popping,” or feeling that the knee is stuck or might pop if moved. Patients with a true mechanical block (which often requires surgical intervention) often say they can unlock the knee by massaging or moving it in a certain manner. Subjective symptoms are frequently caused by damage to the articular cartilage (for which surgery is generally not required).

- Jackson JL, O’Malley PG, Kroenke K. Evaluation of acute knee pain in primary care. Ann Intern Med. 2003 Oct 7;139(7):575-88. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-7-200310070-00010. PMID: 14530229.