Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tear

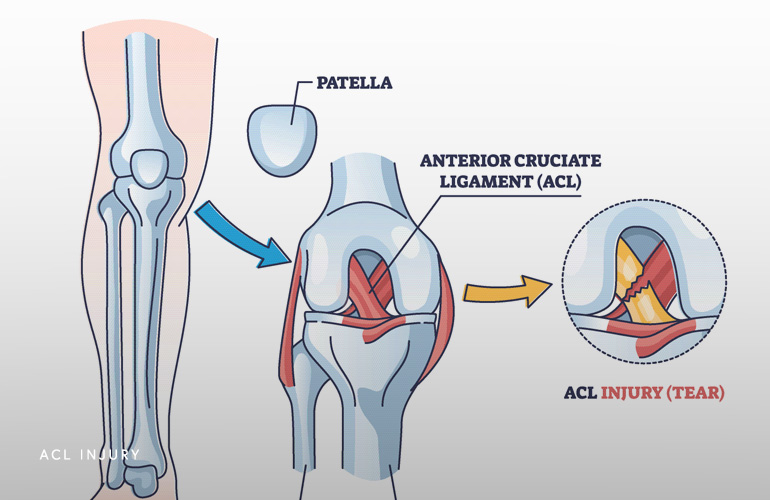

Anatomy

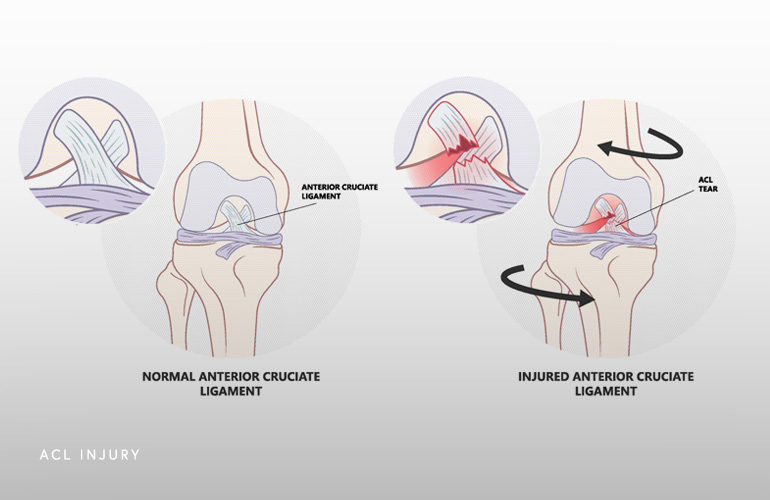

The primary function of the anterior cruciate ligament (“ACL”) is to control anterior translation (forward shifting) of the tibia (shin bone). The ACL also plays a critical role for stabilizing tibial rotation (twisting), which is a function for sporting activities and those involve shifting bodyweight for sports and other activities. The ACL is one of two cruciate ligaments deep in the knee that form an “x”, with the ACL in the front. Without the ACL, the knee is prone to abnormal movement of the bones relative to one another, leading to “giving out”, apprehension (nervousness) about particular activities, and potentially future wear and damage to other tissues in the knee joint.

The ACL is the most commonly injured knee ligament. In the United States there are between 100,000 and 200,000 ACL ruptures per year, so it is a very common injury(1). The majority of ACL tears occur from noncontact sporting injuries but can occur from a variety of mechanisms, including taking a misstep down the stairs or bracing during a car accident. Data from the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) suggests American football players sustain the greatest rate of tears, followed by female sports including soccer and gymnastics(2).

Patients who sustain an ACL injury often complain of feeling a “pop” in their knee at the time of injury, followed by rapid development of swelling thereafter, and a feeling that the knee is unstable or “giving out.” Nearly all patients with an acute ACL injury manifest a unique type of swelling in the knee called an “effusion”, which means fluid in the joint. This effusion develops because the ACL has a blood supply and rupture of it causes bleeding into the joint.

The swelling after an acute ACL tear will gradually resolve and walking will get easier. The knee will remain unstable as activities improve, manifesting as a feeling as though it will give way. Activities involving movements where the entire body weight is placed on the one affected leg will elicit instability symptoms. These movements include going up/down the stairs, squatting, shifting, pivoting on a planted foot, and stepping laterally.

One of the reasons MRI imaging is typically recommended in the setting of an acute (fresh) ACL tear is the incidence of associated injuries that occur in conjunction with the ACL rupture. Sometimes these associated injuries can be difficult to diagnose on the physical exam of your knee because of the swelling and pain but are important to identify because they can affect the long term function of the knee. Associated tissues that are commonly injured include the meniscus, joint capsule, articular cartilage lining, subchondral bone (bone bruise or fracture), and other ligaments. Higher energy injury mechanisms (like a contact football injury) have a higher incidence of these associated injuries.

Initial management of an ACL tear usually consists of ice, elevation, compression, and sometimes protection of weightbearing with crutches if the knee is unstable. Activities in the acute period are guided based on the exam of the knee and imaging, which informs on whether there is a risk or presence of associated injury to the meniscus or articular cartilage. Sometimes protecting activity in the weeks following the injury are important to avoid the damage from getting worse. Some patients may be referred for physical therapy evaluation to improve motion, swelling, and muscle control, whether surgery is elected or not.

An important feature of the decision on how to definitively treat the ACL tear is the open dialogue between the orthopedic physician and the patient to adequately discuss activity expectations, rehabilitation, and the risks and benefits. While avoiding surgery altogether is always an option, there can be many downside risks in younger, active patients, and it is important these are reviewed.

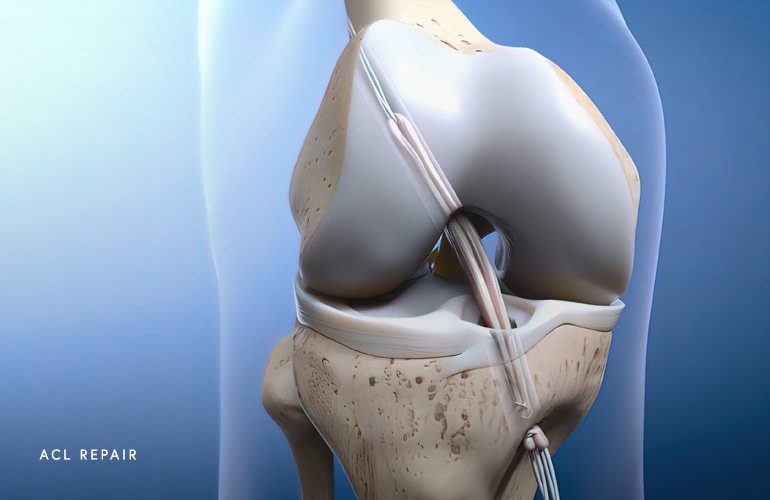

Most active, younger patients and high-level athletes benefit from surgical reconstruction, where the injured ligament is replaced with tissue from another source in the body or from a cadaver donor. Reasons to have surgery include higher level of activity, sporting demands placed on the knee, and the presence of associated injuries to the meniscus or other knee ligaments (eg, the medial collateral ligament). Other factors, such as age and occupation, also play a role. Patients with injuries to multiple knee structures (eg, ACL plus meniscus or medial collateral ligament) generally have a greater need for surgical reconstruction due to the increased instability of the knee. Generally, patient that have a desire to return to high-demand sports or occupations involving cutting, pivoting, or quick deceleration or that experience instability symptoms with simple activites (such as giving out while walking up the stairs) will benefit from surgical reconstruction.

If the decision has been made to treat the ACL rupture nonoperatively, it is important to understand the sequelae and risks. Living with an ACL tear long term (called the ACL-deficient knee) comes with risks of chronic knee pain, decreased activity, and increased risk of articular cartilage and meniscus tear(3). Living with an ACL-deficient knee may increase the risk of osteoarthritis and studies are ongoing. There are patient-specific issues that may influence your particular risk of developing the above conditions if you choose to not pursue surgical reconstruction and it is important you discuss these issues with your doctor.

All ACL reconstructions are performed arthroscopically, with the “scope”. One of the important decisions to make that knee surgeon Dr. Obermeyer will discuss with you is choice of the source of the tissue used to replace the torn ligament. Most of the time, there are factors unique to you that dictate where the donor tissue ideally comes from, including prior injury, age, activity status, etc., but often you have some discretion about what tissue to use.

Both native (autograft) and cadaver (allograft) tendons can be used for ACL reconstruction. Autografts may be taken from your patellar tendon, hamstring (semitendinosus and gracilis), or more recently the quadriceps tendons. Most young athletes who participate in high-risk sports receive autografts. The advantages of autografts include faster healing, lower risk of reinjury, and no risk of infection from graft tissue. Disadvantages include harvest site morbidity which sometimes can generate chronic discomfort with kneeling, longer time in surgery, and constraints around tissue choice (eg, size, harvest site).

Allografts function well for slightly older athletes who have a lower risk of reinjury and are interested in the easiest, most noninvasive surgery. In most ways, allografts perform comparably to autografts, but rates of reinjury of the reconstructed ACL are higher in very young patients, which make allograft surgery a less optimal choice in these patients(4). The advantages of allograft include reduced surgical time, reduced harvest site morbidity, and access to a range of sizes.

Some evidence exists that delaying surgery a few weeks after the initial injury may be advantageous. Doing a course of “prehab” consisting of preoperative physical therapy to eliminate swelling, improve range of motion, and strengthen muscles may result in the best outcomes. However, waiting too long may result in other tissue injuries, especially to the meniscus, and anything greater than three months may heighten this risk substantially(5). If you have associated acute injuries in the knee identified on MRI, proceeding to early surgery may improve the ability to repair damaged tissues.

Schedule an orthopedic appointment

If you have symptoms consistent with an ACL Tear, call our office or book an appointment with knee surgeon Dr. Thomas Obermeyer. Dr. Obermeyer specializes in diagnosing and treating ACL injuries. Dr. Obermeyer has orthopedic offices in Schaumburg, Bartlett, and Elk Grove Village, Illinois. Dr. Obermeyer regularly sees patients from throughout Illinois including Hoffman Estates, Palatine, Elgin, Streamwood, Arlington Heights, and Roselle communities.

- Evans J, Nielson Jl. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Knee Injuries. [Updated 2022 Feb 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499848/

- Agel J, Rockwood T, Klossner D. Collegiate ACL Injury Rates Across 15 Sports: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System Data Update (2004-2005 Through 2012-2013). Clin J Sport Med. 2016 Nov;26(6):518-523. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000290. PMID: 27315457.

- Øiestad BE, Engebretsen L, Storheim K, Risberg MA. Knee osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2009 Jul;37(7):1434-43. doi: 10.1177/0363546509338827. PMID: 19567666.

- Widner M, Dunleavy M, Lynch S. Outcomes Following ACL Reconstruction Based on Graft Type: Are all Grafts Equivalent? Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2019 Dec;12(4):460-465. doi: 10.1007/s12178-019-09588-w. PMID: 31734844; PMCID: PMC6942094.

- Prodromidis AD, Drosatou C, Thivaios GC, Zreik N, Charalambous CP. Timing of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction and Relationship With Meniscal Tears: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2021 Jul;49(9):2551-2562. doi: 10.1177/0363546520964486. Epub 2020 Nov 9. PMID: 33166481.

At a Glance

Dr. Thomas Obermeyer

- 15+ years of training and experience treating complex shoulder and sports medicine conditions

- Expert subspecialized and board-certified orthopedic care

- Award-winning outstanding patient satisfaction scores

- Learn more